Financial services and insurance have been the big drivers of “inflation” beyond energy. The Fed strongly influences financial product prices. If the Fed fears overheating, rather than hiking the Federal Funds rate, it could reconsider its own influence.

Is the Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) Implicit Price Deflator the best measure of “inflation?” The PCE deflator is a broad weighted-average of consumer price changes. The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) relies heavily on the PCE deflator for determining Federal Funds rate increases. But, given the institutional infatuation with the broad average of the PCE deflator, care is needed in interpretation.

Our friend, Chris Whalen, top bank analyst at the Institutional Risk Analyst reminds us, “To avoid skews and biases, avoid confusing price change from non-monetary causes such as technology and other government policies with monetary-causes such as the Federal Funds rate and money supply. The FOMC can’t fix a non-monetary cause with monetary policy. For this reason, food and energy are excluded from ‘Core PCE.’ Health care has a caution flag because of the impact of regulatory policy. For similar reasons, financial services should be added to the caution list.”

In “Concentrated price changes mean less control for the Fed,” data revealed that price level increases since 3Q2016 have been heavily driven by energy plus a boost from services.

Using a bubble chart, within services the inflation villain was found in a few financial services categories that have been fast-growing in price and large in amount purchased. These include services bundled into loans and deposits at commercial banks, auto insurance, and portfolio management and investment advice.

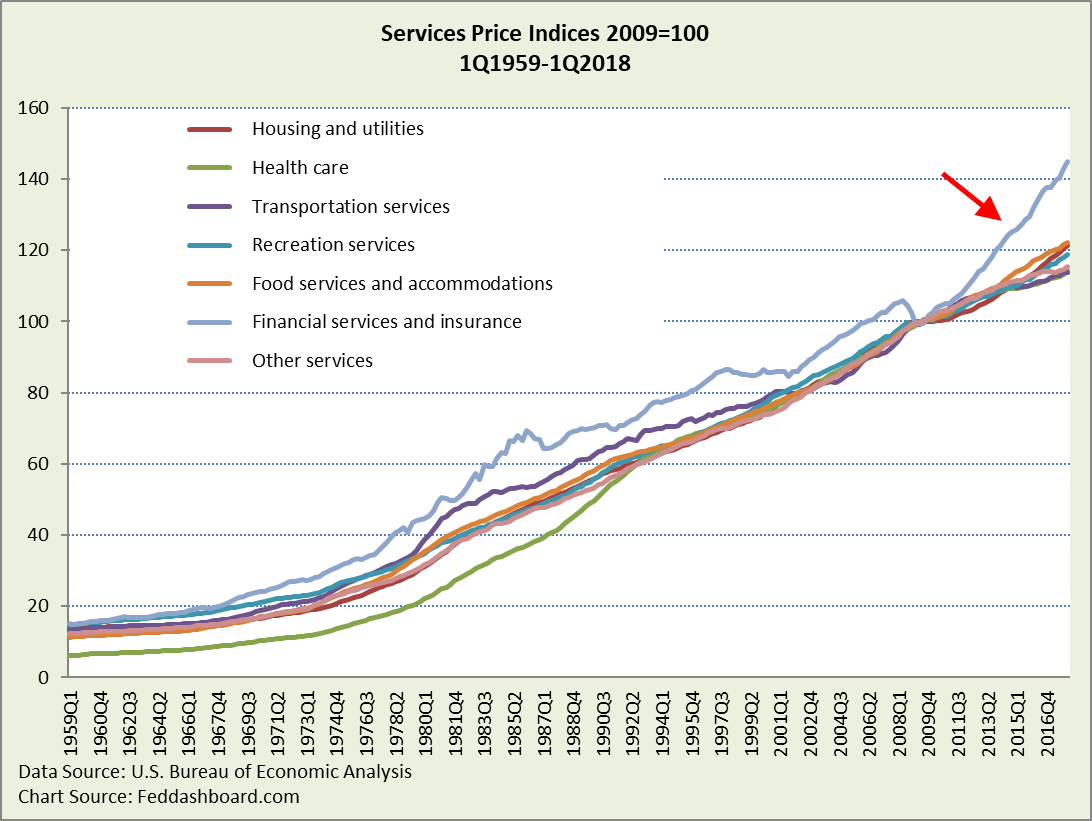

Now, in a line chart, the Financial services and insurance category sharply stands-out from other services.

Rising prices in Financial services and insurance far surpass the “usual suspects” — housing and health care.

Rising prices in Financial services and insurance far surpass the “usual suspects” — housing and health care.

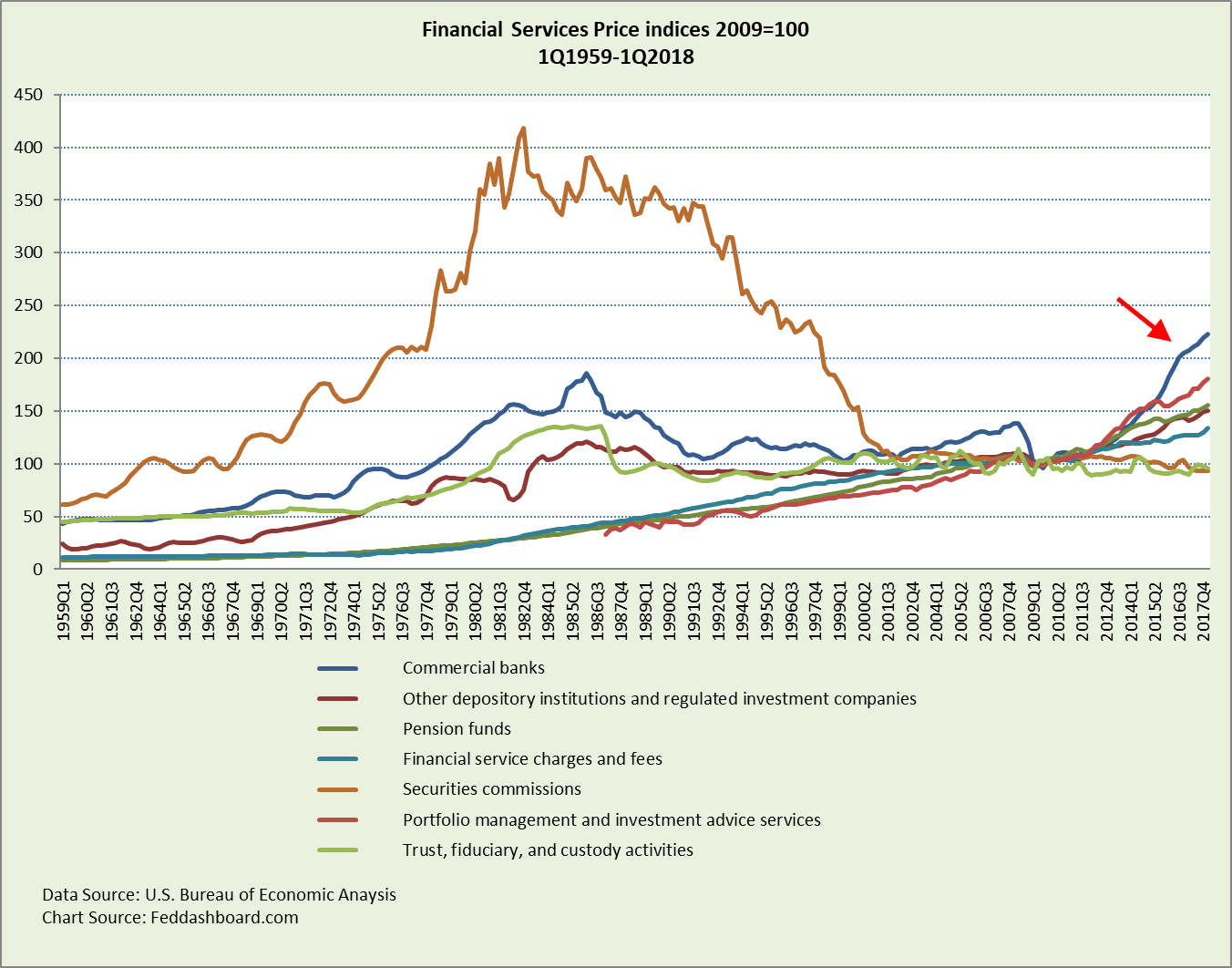

Within Financial services, the fastest recent price growth has been for financial services paid for through savings or loan interest (rather than direct fee-for-service) at Commercial banks, Other depository institutions (savings banks and credit unions) and regulated investment companies, and Pension funds. Next fastest are Portfolio management and investment advice services, and Financial service charges and fees (primarily checking account and other bank service fees).

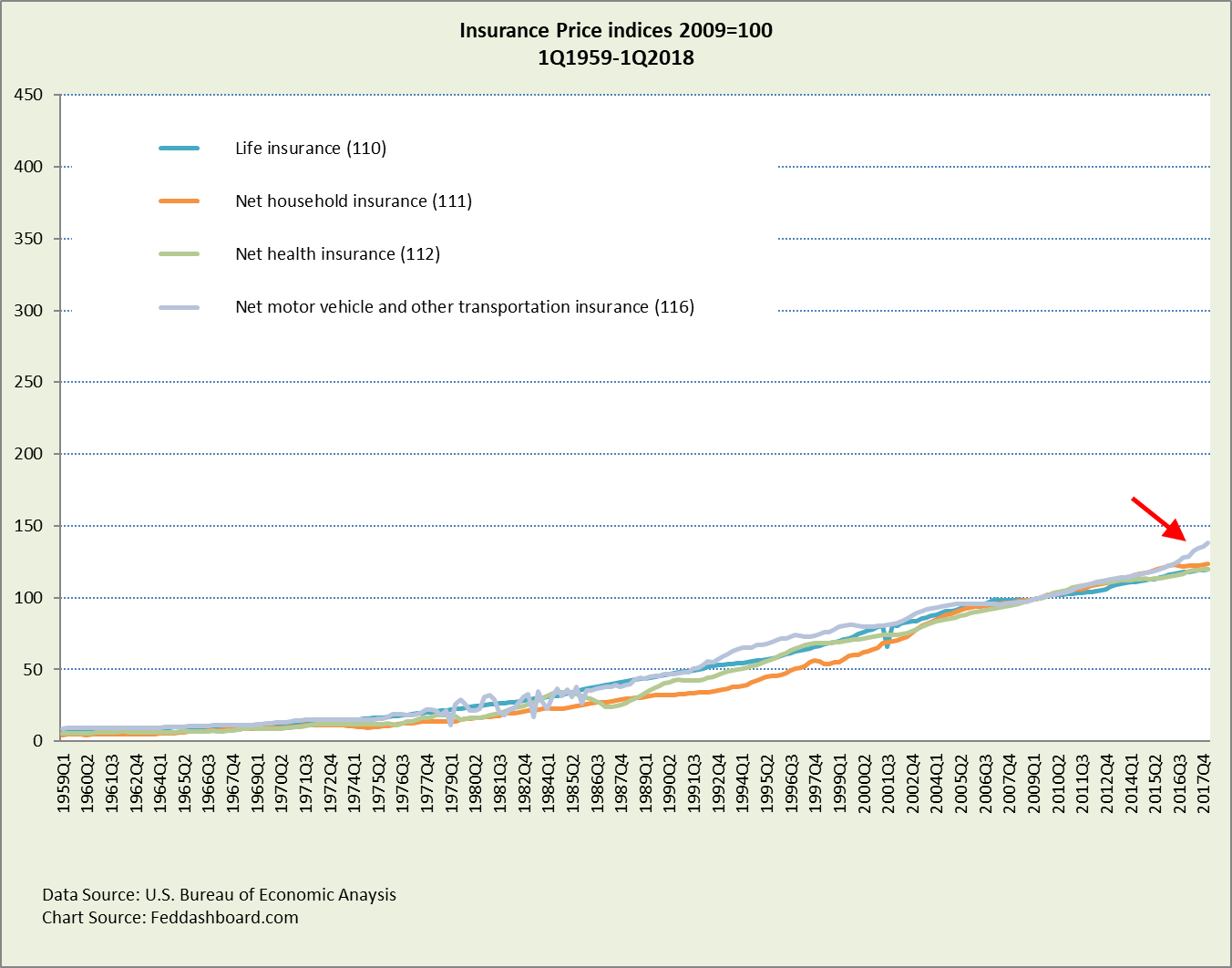

In insurance, the fastest recent price growth has been Motor vehicle and other transportation insurance.

In insurance, the fastest recent price growth has been Motor vehicle and other transportation insurance.

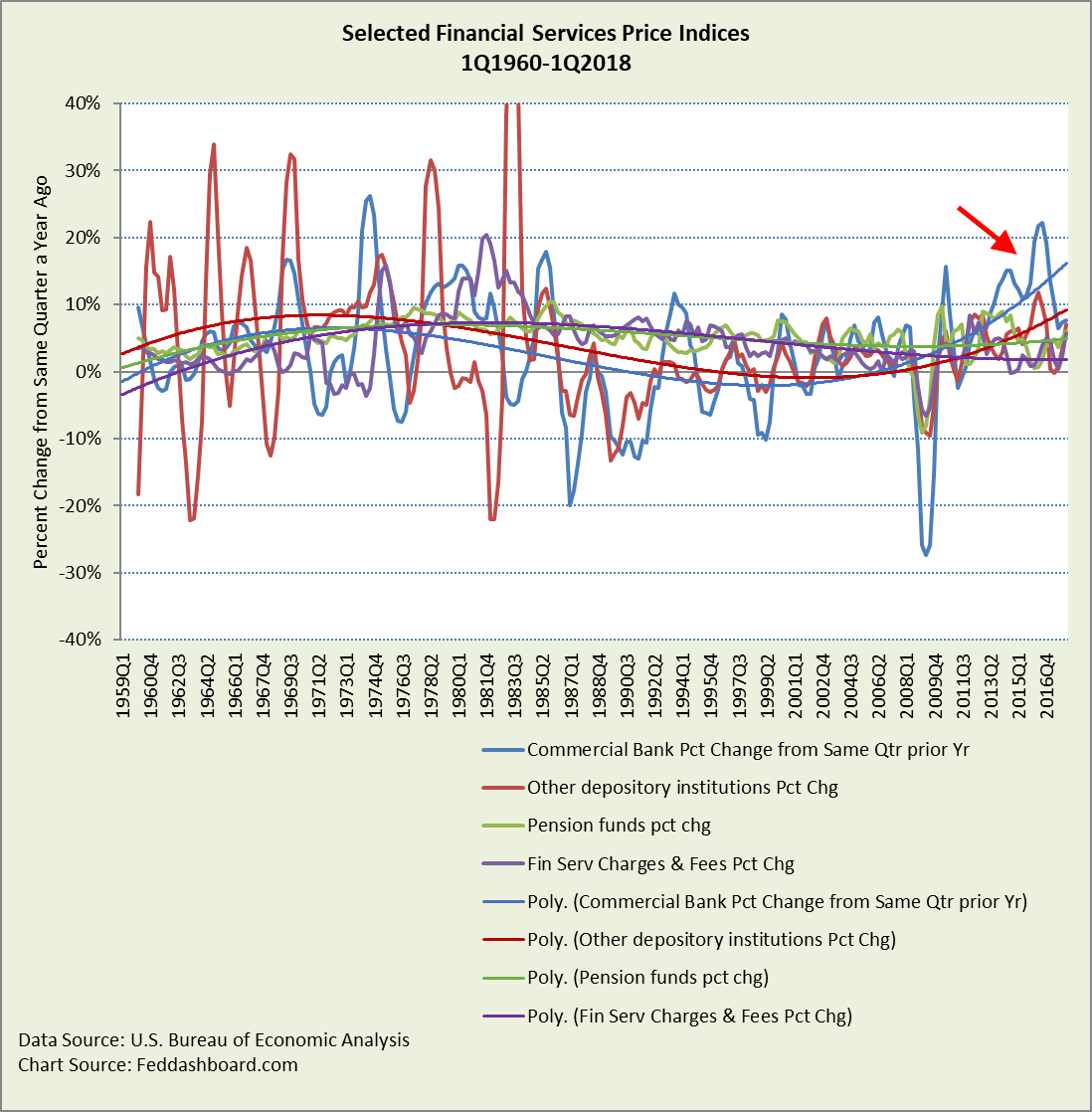

Switching to percent change from the same quarter a year ago, the interplay and magnitude of the growth are easier to see.

Switching to percent change from the same quarter a year ago, the interplay and magnitude of the growth are easier to see.

Financial services and insurance in the PCE deflator excluding food and energy (Core PCE), have been growing 3-4 times faster than the Core PCE deflator. In addition, its weight in the Core PCE deflator is near its all-time high.

Financial services and insurance in the PCE deflator excluding food and energy (Core PCE), have been growing 3-4 times faster than the Core PCE deflator. In addition, its weight in the Core PCE deflator is near its all-time high.

For 1Q2018 compared to the same quarter a year ago, Financial services and insurance contributed about 48 basis points to the Core PCE deflator increase of 1.66%. The full PCE deflator increase was 1.8%.

![]() Central bank influence on product prices in general has been increasingly limited since the 1980s. Their most effective actions to push-up product prices have been:

Central bank influence on product prices in general has been increasingly limited since the 1980s. Their most effective actions to push-up product prices have been:

- What they buy with large-scale asset purchases (commonly known as “quantitative easing” or “QE”). In the U.S., the Federal Reserve System buying agency mortgage-backed securities (AMBS) increased housing prices.

- Foreign exchange rates to “import inflation” because foreign products are costlier in terms of a weaker domestic currency

- Using financial services regulatory power to push-up prices of financial products

Of course, central banks’ QE can powerfully raise asset prices, especially equity markets, and those bonds most closely linked to a policy rate (Federal Funds rate in the U.S.).

Concentrations of product prices within financial services reinforce a familiar story:

- Product price increases are highly concentrated and product price trends widely different, limiting a central bank’s control of product prices because monetary policy is a blunt instrument

- Central bank efforts to target an average price level (2%) are frustrated because product price trends are so divergent

- To the extent any central bank attempts to raise an average price level in such a situation, inequities and misallocations naturally result

The circular game

The Fed has both monetary policy and regulatory arms. Especially since 2009, the regulatory climate has tended to increase prices, especially through risk-based pricing of specific products and passing through compliance costs. In the 1980s and 90s, the emphasis was on lower prices for consumers through competition.

The price for financial services paid through interest, rather than direct fee, is roughly the margin between either deposit or lending rates (depending on the service provided) and a “reference rate” of earnings on Treasury securities. These rates – in varying degrees – are influenced by the Federal Funds rate, increasingly implemented through Interest on Excess Reserves (IOER). These margins, after smoothing, adjustments such as default rates, and comparison to transaction counts then flow to PCE deflator. This one element of the overall Financial services and insurance category is 3.1% of PCE, 3.5% of Core PCE, and 4.6% of Services.

If banks more than proportionally pass-through higher rates and costs in loan rates, or less than proportionally raise deposit rates, then the PCE deflator is pushed up.

This becomes a circular game when the FOMC is observing its own behavior – whether regulatory or monetary. Again, this is similar to Fed purchases of AMBS on housing prices.

Given the rising PCE deflator and the Fed’s own role in that rise, how should the monetary policy arm react? The FOMC could:

- Welcome the price increase when it helps the average price level change reach the 2% target

- Ignore it because it is concentrated so an average price level increase of “inflation” is mathematically meaningless because of the wide dispersion of prices

- Fear it when it exceeds the 2% target, so increase the Federal Funds rate

- Ignore it because either the regulatory arm can tactically change the regulatory climate or the change is an echo of the monetary policy arm setting the Federal Funds rate

For investors, it would be helpful if the FOMC members stated how financial services and insurance prices, especially implicit prices paid through interest charges, will affect Federal Funds rate decisions.

To learn more about how to apply these insights to your professional portfolio, business or policy initiative, contact “editor” at this URL.

Data Geek Notes:

- For the Bureau of Labor Statistics method, see Royster, Sara E. “Improved measure of commercial banking output and productivity,” Monthly Labor Review, July 2012

- In the 2013 comprehensive revision of the U.S. National Income and Product Accounts, the Bureau of Economic Analysis introduced improved methods for measuring the implicitly priced services provided by commercial banks. See Kyle K. Hood, “Measuring the Services of Commercial Banks in the National Income and Product Accounts: Changes in Concepts and Methods in the 2013 Comprehensive Revision,” Survey 93 (February 2013): 8–19.

- For the methods of imputing prices, see Passero, William, Garner, Thesia I., and McCully, Clinton. “Understanding the Relationship: CE Survey and PCE.” U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics Working Paper 462, March 2013