Central Bank interest rate actions have little control over price changes due to digital shopping, demographics, better management, technology, or government policy (tax, spending and regulation). So, they can stop trying to raise interest rates out of fear of, say, apartment rents in San Francisco.

With a big day in football coming up, consider special teams – experts at kicks, punts, and returns. They are vital when called on the field and can make magic moments. But, for most of a game, they’re only watching. While watching, they avoid stressing about the rest of the game, so they can focus on their mission.

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) likewise can avoid excessive worry about “inflation” from causes beyond their legal authority or capability of their tools. Their tools are primarily the Federal Funds rate, money supply, and large-scale asset purchases (a.k.a., Quantitative Easing, QE).

Causes beyond the FOMC include the actions of shoppers (digital and global shopping, and living preferences), producers (especially in management technique, technology and global sourcing), and other government policy (taxing, spending, and regulatory). The power of these causes is seen in economic and business data – especially that price changes are highly specific to product and location. This data is in stark contrast to theory suggesting that product prices mostly move together and are mostly due to monetary causes (interest rates and money supply).

Instead, data show that “inflation” affects people very differently depending on what they buy and where they live. Because FOMC tools are blunt instruments, the FOMC has increasingly become an engine of inequities and distortions – redistributing money via interest rates and prices. For example, for rising interest rates, the people hurt most tend to be those with loans most tied to the Federal Funds rate. For these people, global lending platforms offer hope.

Price changes are specific to products

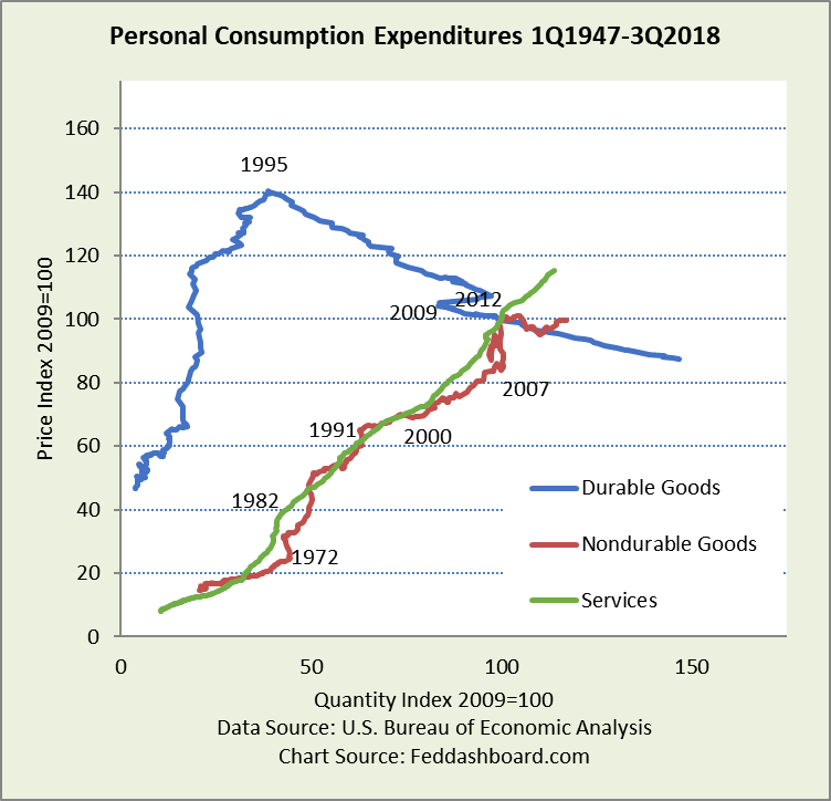

Trends for durable goods, nondurable goods, and services are strikingly different.

In this classic “Econ 101” price-quantity scatter plot, it’s also clear that amount purchased is different. For goods, shoppers buy more when prices fall. For durables, this has been an over two-decade trend. Previously, we’ve explored the data to reveal fascinating stories of real people buying real products, such as in “It’s not secular stagnation; it’s the tech and trade transformation.” Here, we’ll just look at product categories.

In the past two years, the FOMC has become more concerned about rising prices. Previously, we looked at the May data. Below, is an update.

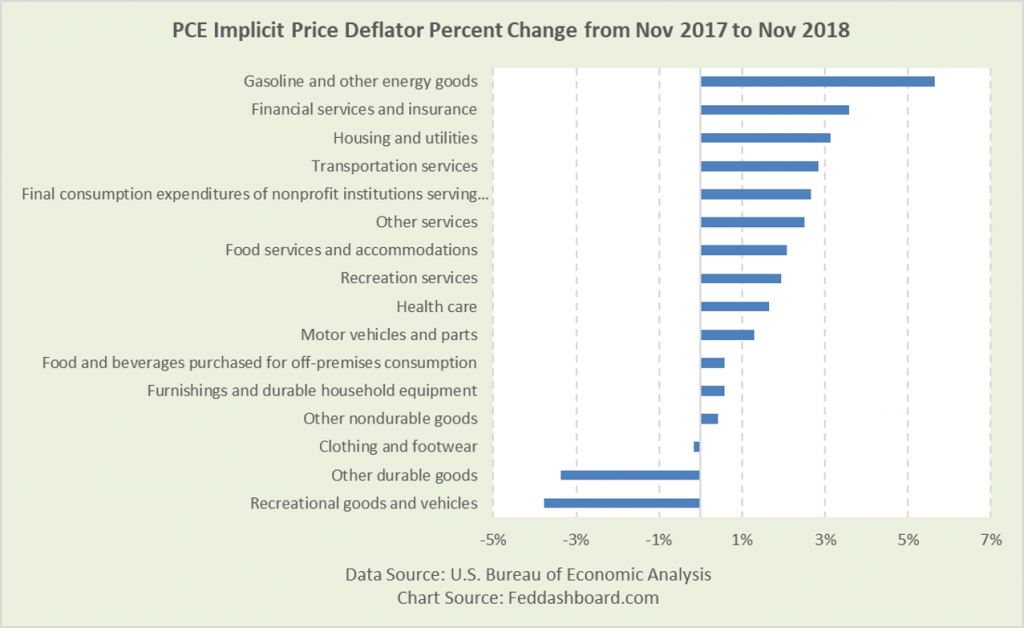

First, the view of a shopper — percent changes…

Gasoline is the biggie, with relief in recent months.

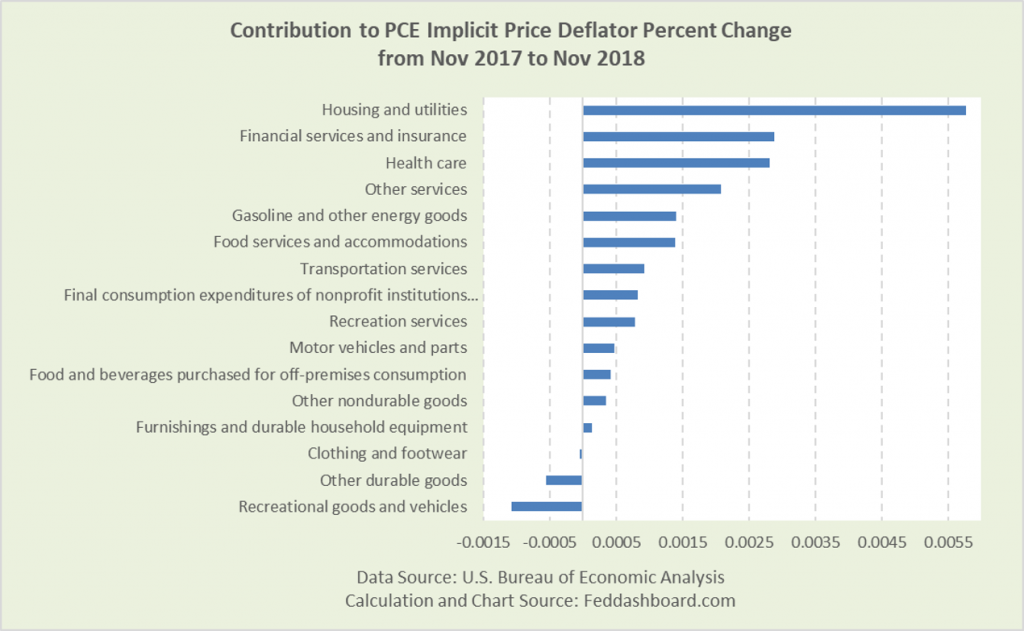

Second, the view of the price deflator index that is weighted by purchase amounts.

Housing and utilities, because of it’s big share of overall purchases, is the biggest influence. But, only renters, not existing homeowners experience that jump.

Consider the next biggest categories, financial services and health care. Both are “soft” estimates, in large part because it is difficult to measure the changes in quality of services received.

- How much better is a diagnostic test or cancer drug?

- Does your hospital or bank’s app have any value to you? Online services aren’t counted. For banking, that’s a big missing piece.

- How should regulation be measured? That was debated decades ago with regard to motor vehicles but is still an open question in financial services. More directly than with monetary policy, the Federal Reserve in its regulatory authority can drive bank margins and consumer prices up or down.

The point is that the FOMC doesn’t need to swing the interest rate club at these because 1) these changes weren’t caused by monetary policy and 2) the FOMC’s tools have nearly nil influence on the causes.

Yet, like the football kicker, the FOMC’s tools have direct effects on:

- Housing prices via mortgage rates via QE purchases of Agency (Freddie & Fannie) Mortgage-backed Securities – countered by increases in the Federal Funds rate

- Import prices via foreign exchange rates, along with the opposite country’s central bank

Digging into business data and equity market industry analyses, stories emerge of the forces that are driving prices. In the past year, trade policy has been widely discussed. Then there are long-term trends of falling costs due to improved management methods and technology – this has been central to company presentations to equity analysts.

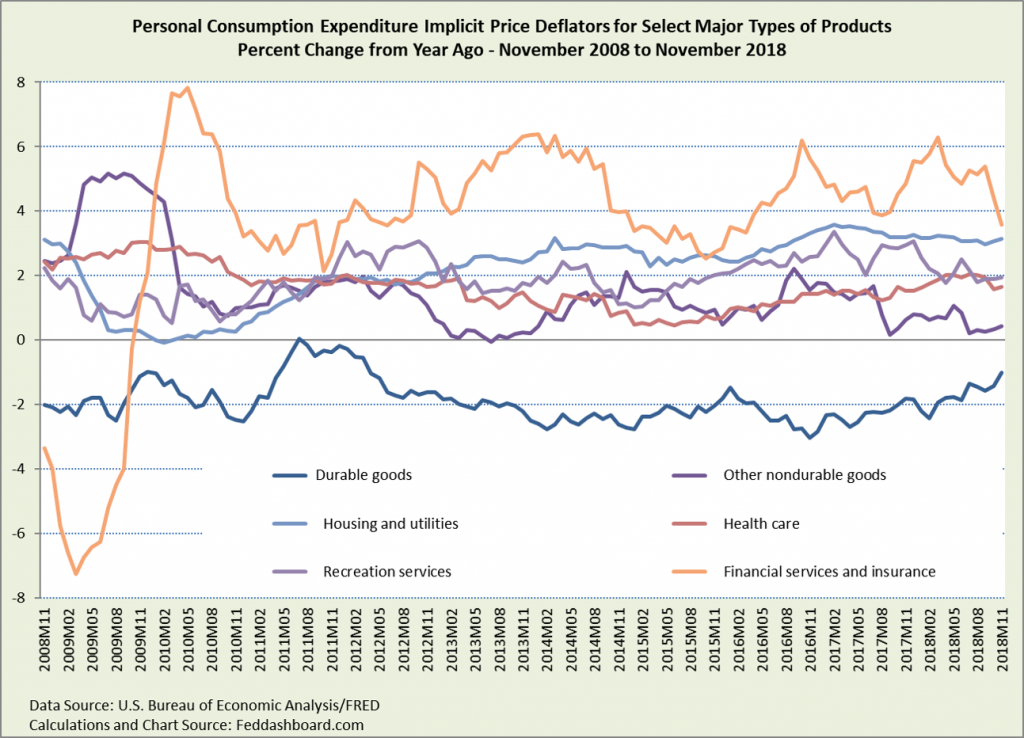

Below, the trend view reveals independent paths for the six largest product categories, excluding food and energy (other than housing utilities).

Importantly, the price trends are quite independent – undermining the view that product prices mostly move together and thus price level change is mostly from monetary causes.

Previously, we’ve illustrated how the PCE deflator has fallen even when the monetary base has increased and fallen when Total Financial Assets have increased. Forces at work are more powerful than money supply.

There is a warning sign for the FOMC in the durable goods uptrend since fall 2016. What’s the cause? How much is foreign exchange rates, trade policy, increasing domestic retail costs, margins, and other?

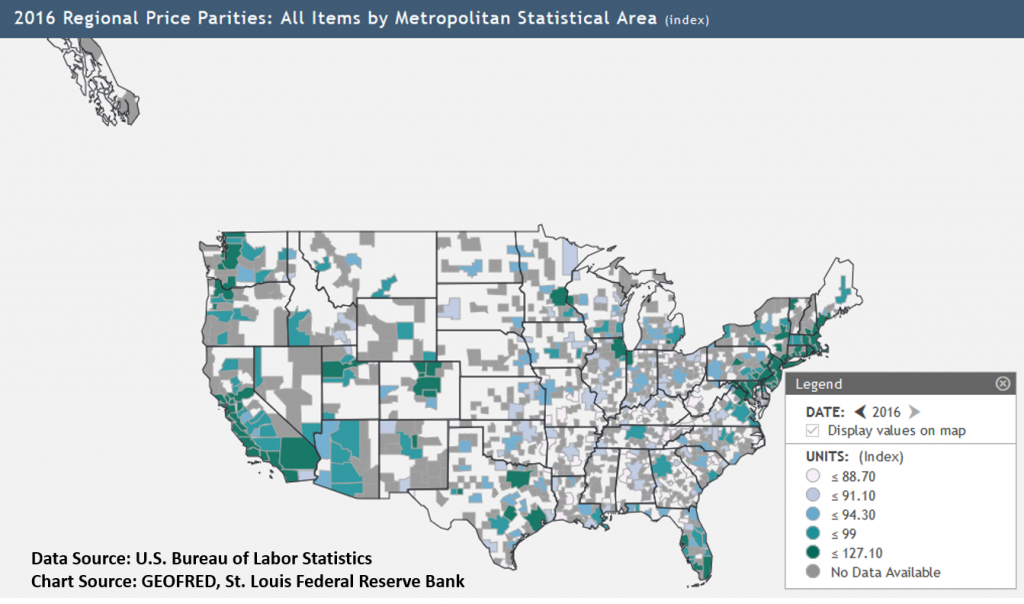

Price changes are specific to location

Beyond housing prices, local forces from demographics to regulation act on prices. Higher real estate values and rents increase prices of bananas and more. The FOMC can’t fight urbanization.

Yet, not included in official data, digital shopping and global sourcing offer urbanites the same prices as someone in Iowa – leading to many package deliveries and boxes to be hauled away.

Shifting from scarcity to abundance

The easy purchase of the packages above reflects a shift from scarcity to abundance — made possible by the global tech and trade transformation. Abundance brings a new reality to economic theories that assume scarcity.

- Lower prices are assumed bad because theory says they imply weak demand. Data says, not really true – shoppers buy more when prices fall – that’s Walmart. Business data says prices are falling with falling costs, digital shopping, and global markets.

- Higher prices are assumed bad because theory says, “too much money chasing too few goods” and “overheating.” Data says, not really true as mentioned above. Further, higher prices aren’t a monetary problem if margins are increasing for product differentiation (think Starbucks coffee or Nike shoes), for non-monetary reasons, or meaningful scarcity (think shifting manufacturing locations due to trade policy or rich people paying more in restaurants that increase restaurant worker wages).

- Scarcity theory tends to hold better in locally provided, regulated and personally differentiated services (think nail salons or accountants). Scarcity theory tends not to hold for globally tradeable goods and services – in econ-speak, as in the first chart, the Long Run Aggregate Supply Curve for durables dissolved over two decades ago – before today’s economics students were born.

Bottom line

- The FOMC can stop worrying about fighting causes of price change it can’t control. Then, more focus can be applied to where it’s tools matter most – just like a football special team.

- In today’s world, a price stability guide-post for central banks in economies with general abundance is price stability in globally tradable goods and services, then adjusting for national influences such as foreign exchange and regulation (including trade policy and wholesale-retail market structure).