The UK is not doomed to EU punishment and economic demise. The UK has negotiating leverage. Two examples – UK net exports and exchange rates — illustrate all is not lost. Indeed the UK may emerge stronger.

“Markets” can get it wrong. Markets generally underestimate the UK’s negotiating leverage, just as they underestimated chances of Brexit and panicked after the vote.

Who has more to lose?

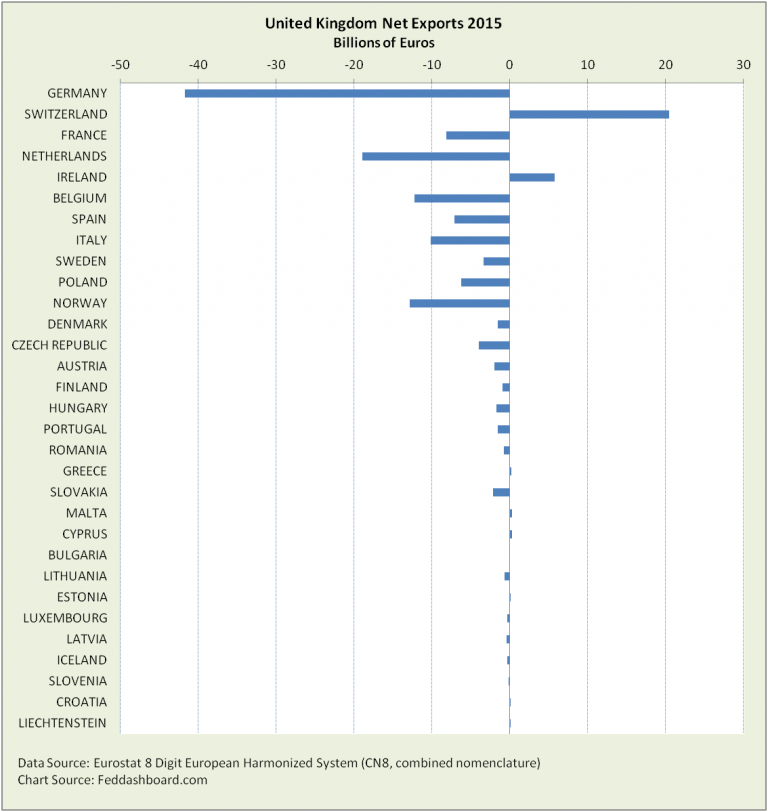

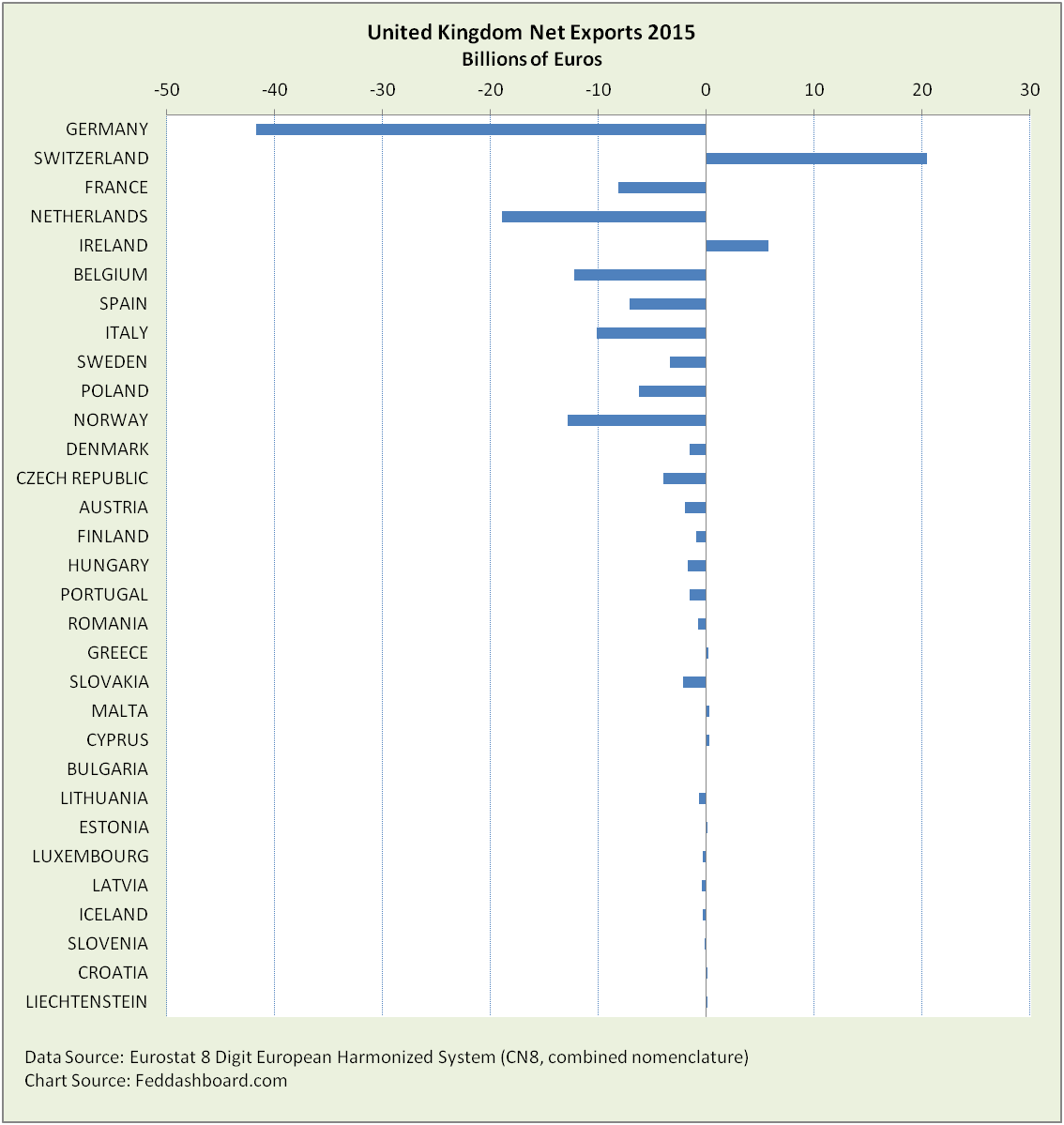

When jobs dominate elections, national exports matter. The UK’s trade deficit with most members of the European Single Market (European Union plus Iceland, Liechtenstein, Norway and Switzerland) means that trade barriers would tend to hurt EU countries more than UK. Economic pain translates to voter pain translates to political leader attention.

In the picture below, UK trade partners are arranged in order of UK’s export size. Negative numbers mean a trade deficit (more imports than exports) for the UK – and by way of consequence, leverage for the UK. Why? Because EU trade restrictions mean the UK could seek similar goods from elsewhere (Commonwealth members, U.S., Japan, China and more). The EU has a bit of leverage because of switching and transportation costs, but that edge is smaller today in our more technology-equipped world than it was before the EU existed.

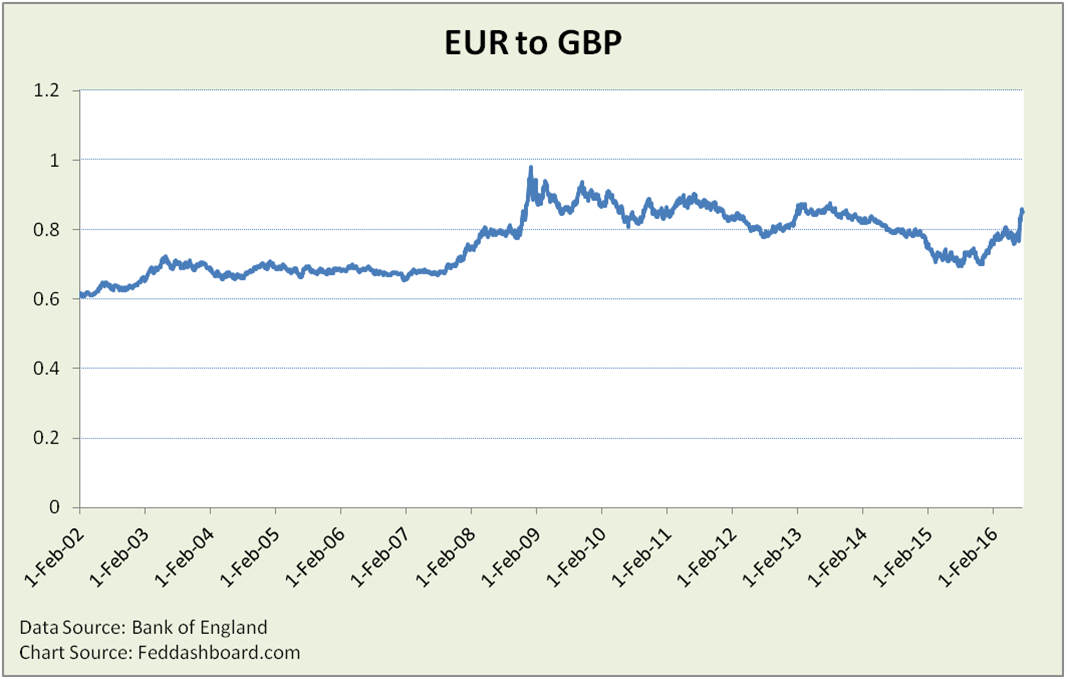

Among the over-reactions in the financial markets was the EUR/GBP exchange rate. Yes, it had been under pressure by the increasingly close vote and yes, it plunged when the vote was announced. But, picturing the data in perspective, this wasn’t devastation. It’s in its post credit bubble crash range – until the European Central Bank started devaluing the Euro in an attempt to import inflation.

What does this mean?

What does this mean?

- For monetary policy, it hurts Governor Draghi’s efforts to import inflation.

- For tangible products, it increases the cost good imported from the Euro area to the UK. This means UK residents will tend to cut discretionary purchases of Euro area goods and services. UK business and residents become more likely to search for lower-priced products from other countries. Who then gets hurt? Euro area businesses and their employees.

Markets have been poor political analysts

In emerging markets, investors have long been highly sensitive to political power and surprises.

In so-called developed markets, politics took on new power in 2008 when central bankers and finance ministers gained more ability to move markets than company fundamentals or price patterns.

Financial and gaming market ignorance was demonstrated in “the market’s” misreading of Brexit polling data. Yougov.com’s excellent analysis describes how markets brushed off multiple warnings, including a two point lead for “Leave” three days before the vote. The market’s problem was more than ignoring data; it was also allowing emotional/political bias into trading models.

Further, “markets” don’t really understand themselves. Markets assumed financial companies would flee London. They didn’t ask, “Why is finance in London?” It’s there because that’s where the liquidity is, not because bankers like the cultural wealth or world food. More, leaving London increases exposure to Euro area banking problems, and increasing regulation or tax.

Markets must learn about leverage

Data can clarify the game board and existing leverage, but political decisions are the game. Poor political decisions can squander leverage. Good political decisions can both build new leverage and extract the most value from leverage.

Leverage can be managed with both classic and newer, creative plays. Prime Minister May and Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union David Davis have already revealed at least three. First, create greater internal unity than the opponent. This is seen in how she flies a “one nation” flag and selected her cabinet. Second, let time weaken the opponent. While the UK faces an EU deadline, EU leaders – with diverse objectives – have to face elections amidst ongoing migrant and financial turmoil. Third, grow non-EU trade agreements. This has been in David Davis’ playbook for years.

Investors and traders can sharpen their political analysis by asking four questions:

- What is the design wisdom and current health of the process by which each government (and the EU apparatus) will arrive at its decisions?

- What are the opportunities and threats facing each decision maker?

- To what is each decision maker structurally blind?

- What are the objectives of each individual and group decision maker through whom the decision process flows?

Bottom Line for investors

- The UK has strengths demonstrated in data. Heavily discounting UK strengths was an error.

- Be cautious of political decisions and market commentary devoid of solid data

- “The market” makes political mistakes, exploit its structural blindness – particularly when based on sentiment rather than fundamental data

Data Geek Notes:

- There are multiple international trade measures, observers have been confused by this, carefully check definitions

- Intra-Europe trade numbers can be significantly influenced by country VAT and small volume/high value flows in industries such as aerospace.