Productivity is not designed to measure technology improvement. Investors, avoid the price-productivity assumption when forecasting “inflation.” Instead, look at more direct links between the global tech and trade transformation and prices.

Analysts trying to explain the weaker growth in product prices often reject tech improvement as an explanation because measured productivity growth has been weak. This approach makes assumptions that – you guessed it – aren’t quite true, such as:

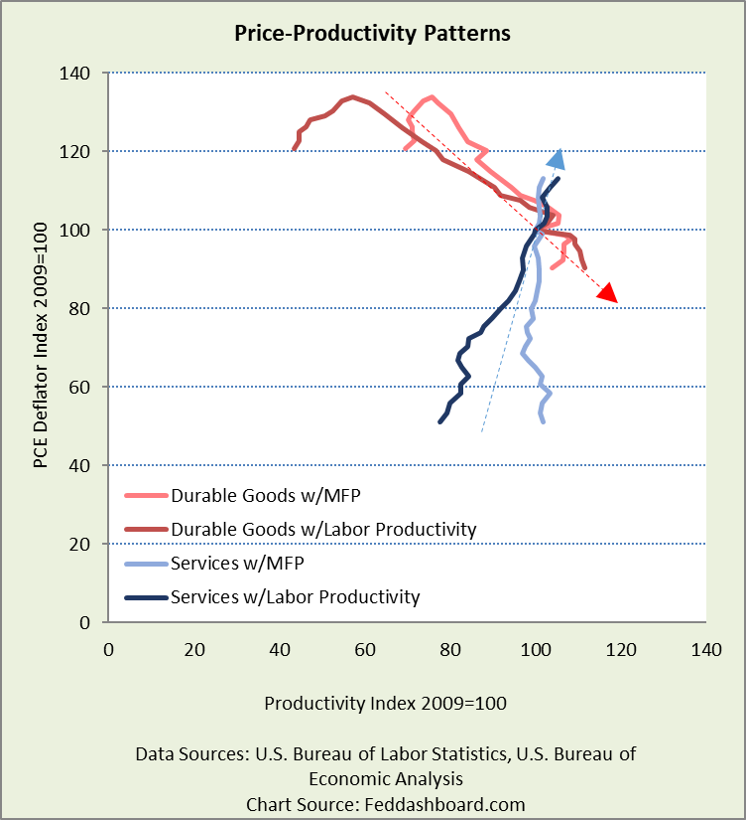

First, assumes a consistent trend in productivity gains and lower prices. The Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS) has published data on durable goods manufacturing and services from 1987 to 2015. Notice how the trend for durable goods is generally downward-sloping since 1995. But, the trend for services is upward. While durables have the assumed trend, services do not.

Services multifactor productivity has changed little in three decades. Services expenditures are 6.2 times the size of durables, up from 4.2 in 1987. Services productivity is far more difficult to measure. Thus, the services trend increasingly hides the durables trend.

Services multifactor productivity has changed little in three decades. Services expenditures are 6.2 times the size of durables, up from 4.2 in 1987. Services productivity is far more difficult to measure. Thus, the services trend increasingly hides the durables trend.

Productivity growth by industry varies dramatically as we previously showed in this chart.

These differences mean there’s more to the story.

Second, assumes “productivity” measures technology improvement. Not really. Productivity is the math result of comparing output to a defined set of inputs. Whatever output gain is not in the inputs is deemed “productivity.” This productivity measurement is different from the more straightforward advice at the Henry Ford Trade School, “work smarter, not harder.”

- Labor productivity compares labor hours as the input to output. All other inputs and environment conditions (from storms to regulations) can also be changing. As we’ve shown previously, the weakness in labor productivity since 2009 is mostly about labor hours rebounding. Hours worked have especially grown in food services and drinking places, and outsourcing (administrative and support services, and business, scientific and technical services).

- Multi-factor productivity (MFP) compares several inputs (structures, equipment, intellectual property, labor, energy, materials and purchased services) to output. Each input reflects technology. But, more inputs mean more measurement complications. There are catalogs of complications. We’re most intrigued by four: 1) growth of outsourcing and offshoring for lower wages, 2) strong productivity growth of structures (buildings), 3) difficulty measuring quality improvement in equipment, and 4) the intellectual property products (IPP) problem.

With the “red dots,” we illustrated how faster growing imports tend to have slower price increases.

The IPP problem arises because the more IPPs are counted to boost Gross Domestic Product (GDP), the more they become an input to production that can lower the MFP rather than being part of “smart ideas” (management or worker technique that isn’t counted as an input – thus is part of productivity). IPPs are increasingly counted because of better survey techniques or an accounting situation is triggered (putting an idea into software, filing a patent, claiming research and development costs on tax returns).

Third, assumes the U.S. is the location of both production and sale. The Fed’s preferred price measure is the Bureau of Economic Analysis’ price deflator for Personal Consumption Expenditures, excluding food and energy. Sales are in the U.S., but production can be anywhere. By contrast, productivity is measured for U.S. locations. So, offshoring or reshoring for lower costs can change measured productivity.

Fourth, assumes clarity in measurement complexities that have been debated since Adam Smith. Complexities expanded with the global tech and trade transformation that increased digital technology and global supply chains. In addition to measuring inputs, it’s also about outputs. Outputs are especially difficult to measure in services. Are data services about megabytes or app interface ease of use? Is a doctor visit about minutes, test technology or healing? What’s a university course? This also isn’t new. Measuring a blacksmith hammering out horseshoes 200 years ago had complications from variations in tools, grade of ore, and sufficiency of water – just ask a blacksmith at a living history museum.

So far, this glimpse of data and measurement challenges raises cautions.

More interesting are assumptions about what measured productivity actually observes and implies…

A very small business a story

Imagine a young girl building birdhouses for her family and friends by sawing, nailing, and painting. If one day she switches to 3D (additive) printing, measures of multifactor productivity can drop if:

- Her parents file a patent or claim research and development costs on taxes because she has now turned her brain-driven work methods into software-driven. The more Artificial Intelligence directs workers, the lower measured productivity.

- The government productivity measurement process assigns a higher capital charge and overall cost to her new method, even if her hard costs are less. This might happen because the measurement math underestimates quality improvement in equipment, overestimates depreciation, underestimates net tax cost or underestimates the sharing economy (using a printer in a maker space or library).

Importantly:

- While she experiences hard costs, she isn’t aware of the government measures that count her IPP against measured productivity

- Her decisions aren’t based on government measures. Rather, she probably decides based on how much cash she gets compared to her sales opportunities (finite), how much work she perceives in each method (Is using the printer convenient or does it require travel? Is programming more difficult than sawing?) and whether the printed birdhouses are more attractive to potential buyers.

Fifth, assumes business people measure productivity as economists do.

- Economists prefer to quote top-down measures of productivity such as nonfarm business sector for which “output” is a residual – Real Gross Domestic Product (GDP) excluding General government, nonprofit institutions, paid employees of private households, the rental value of owner-occupied dwellings, and the farm sector. For example, Fed Chair Janet Yellen usually quotes nonfarm business labor productivity. By contrast, business production managers use bottom-up measures of productivity where “output” is physical unit counts. When the BLS publishes bottom-up measures, they use data collected from business locations by the Census Bureau.

- Economists have an increasing tendency to use revenue-per-worker. But, this tends to obscure market segment pricing power, hours per worker, labor sourcing approach and value creation model. Businesses with billable-hour workers can use revenue-per-worker internally because they can adjust with customer bills, people assigned to a project, and full-time equivalents.

Sixth, assumes business people make decisions based on productivity.

- Externally, measured productivity isn’t a standard part of a quarterly earnings release. Public-company Chief Financial Officers (CFOs) are delivering quarterly releases that focus more on gains in earnings or dividends per share and return on equity. Earnings are different from economic profits as fundamental analysts well know.

- Internally, business people are more likely to use measures such as net present value or return on invested capital, often with a payback period. While payback period makes no sense in financial management or economic growth, payback is the sad reality of CFOs living from one earnings release to the next.

- In both views, taxes matter. In private companies, tax minimization is more important.

Seventh, assumes that higher measured productivity also improves measures used for business decisions. Not really, consider…

- A hotel that hires more people for better customer service or faster room turn-around. That lowers labor productivity, but it might improve revenue per room (return on assets).

- A manufacturer that hires people instead of robots lowers labor productivity. A management team might do this because it either delays taking a risk on a big capital decision or provides more task flexibility (until robots improve mobility).

- People are not “invested capital” so return on invested capital measures look better

- A hospital that switches to more per diem workers who don’t receive benefits lowers revenue per employee but can improve earnings

- A company that cannot get equipment financing at reasonable rates, might hire more people to boost capacity

- A company can fire older workers and hire more and younger workers at lower wages, reducing productivity but improving earnings

Universities give degrees in “financial engineering” and departments are in silos. Thus, accounting disconnects between how economists measure “productivity” and business decisions are made should be no surprise.

Better insight into business decisions

For a clearer view of the technology investment process, ask company project managers or technology solution vendors their hurdles to approval in both return on project investment and payback.

- Instructive are the benefits companies could achieve with no new budget if they had both the expertise and culture to fully implement the technology features they’ve already purchased. Consider how few features you use on your smartphone because you don’t prioritize learning time, even if the benefit is high.

- Fundamental investors, look for company ability to prioritize smarter and improve continuously.

In addition to avoiding the price-productivity trap…

- Stop assuming economic growth equals labor productivity growth x labor growth. As we’ve written previously, that formula is increasingly outdated given labor share of inputs falling and global capacity growing.

- Stop following calculations of potential GDP that exclude available capacity, as described in “Potential GDP is potentially misleading”

To learn more about how to apply these insights to your professional portfolio, business or policy initiative, contact “editor” at this URL.

Data Geek Notes:

For more, please see our Productivity Section and our Money & Prices Section

“Total Factor Productivity” is an overly-ambitious name for the more appropriately named “Multifactor Productivity” wisely used by the BLS

Kenneth I. Carlaw and Richard G. Lipsey have written thoughtfully, including: