The Fed bubble reminds people of huge gains and raises fears of a fall. Central bank decisions are just one example of bigger “decision risk” – a few people making errors in high-impact decisions. These risks are increasing. Increasing danger requires a better way of managing risk — that starts with a clearer view of threats.

Like driving in a fog, today’s threats are confusing. Too many individual investors have gone defensive. Some blame “the markets.”

This year will be another of struggle for investors who don’t take the time to understand threats and design portfolios to manage that risk.

Daylight from the data

The picture of nominal market indices shows current price levels towering 50% above past peaks – and brings out emotion. Either you got or missed the gains. Either you are eager for more gains or fear the fall. As this price picture is probably burned into your mind, we won’t repeat it here.

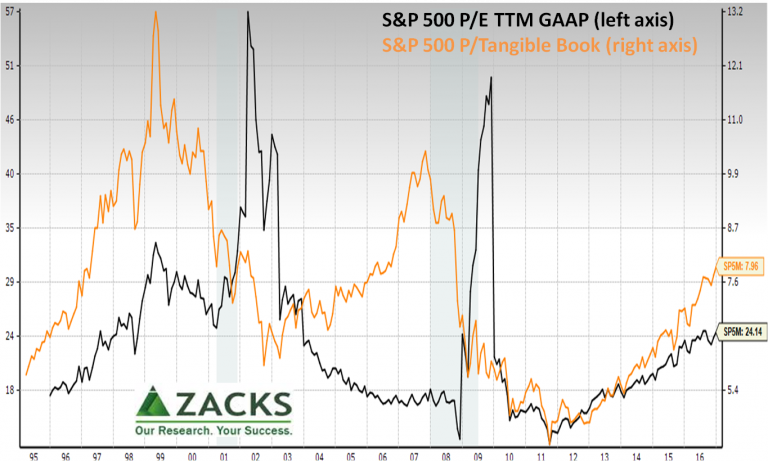

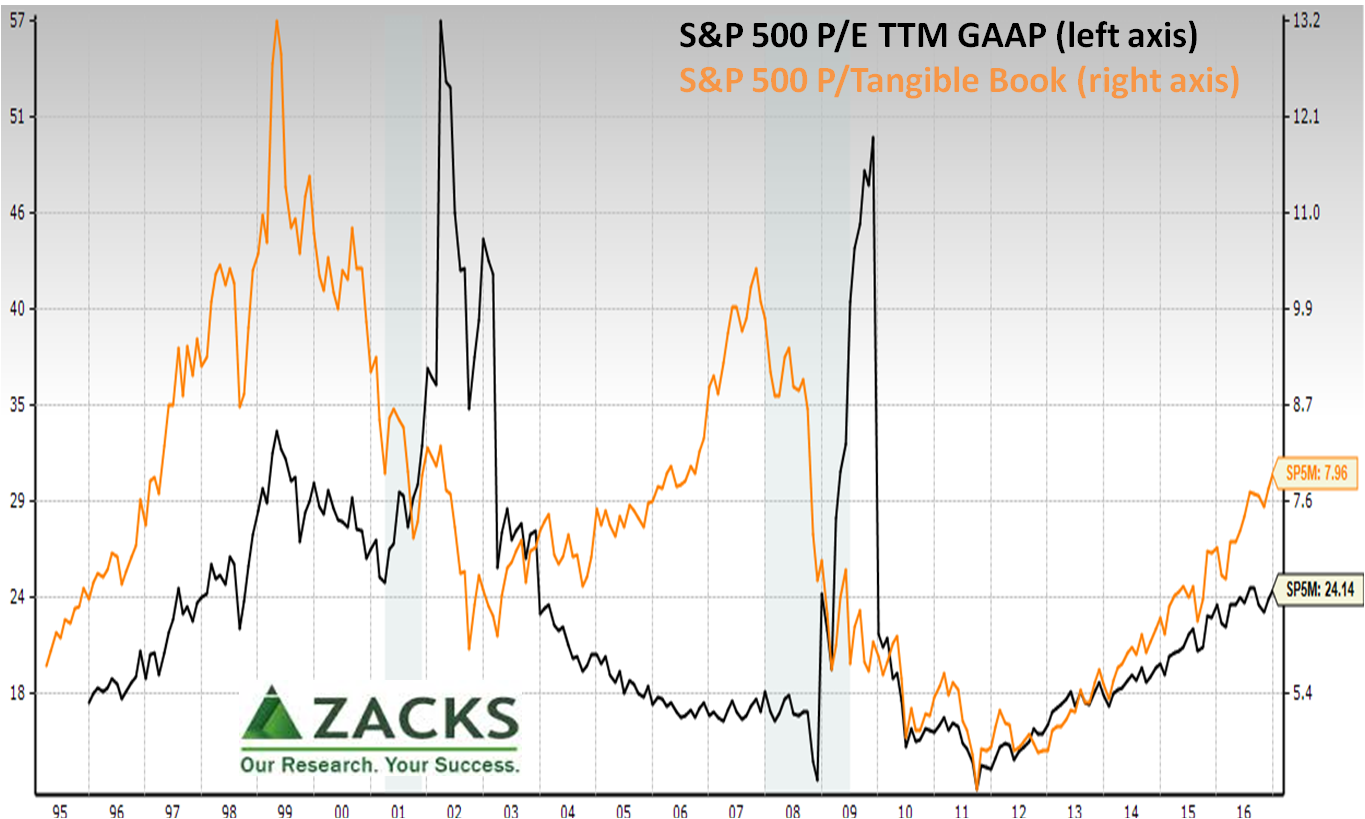

Instead, let’s look at S&P 500 Price/Earnings (TTM GAAP) and Price/Tangible Book.

The P/E is at highs other than “bad times” spikes. Price to Tangible Book was huge during the tech bubble and as the housing bubble burst because of combinations of exuberance and asset write-downs. If one assumes we’re in stable times today, the ratio is rich. If this is an extraordinary time, then use caution for extraordinary reasons.

The P/E is at highs other than “bad times” spikes. Price to Tangible Book was huge during the tech bubble and as the housing bubble burst because of combinations of exuberance and asset write-downs. If one assumes we’re in stable times today, the ratio is rich. If this is an extraordinary time, then use caution for extraordinary reasons.

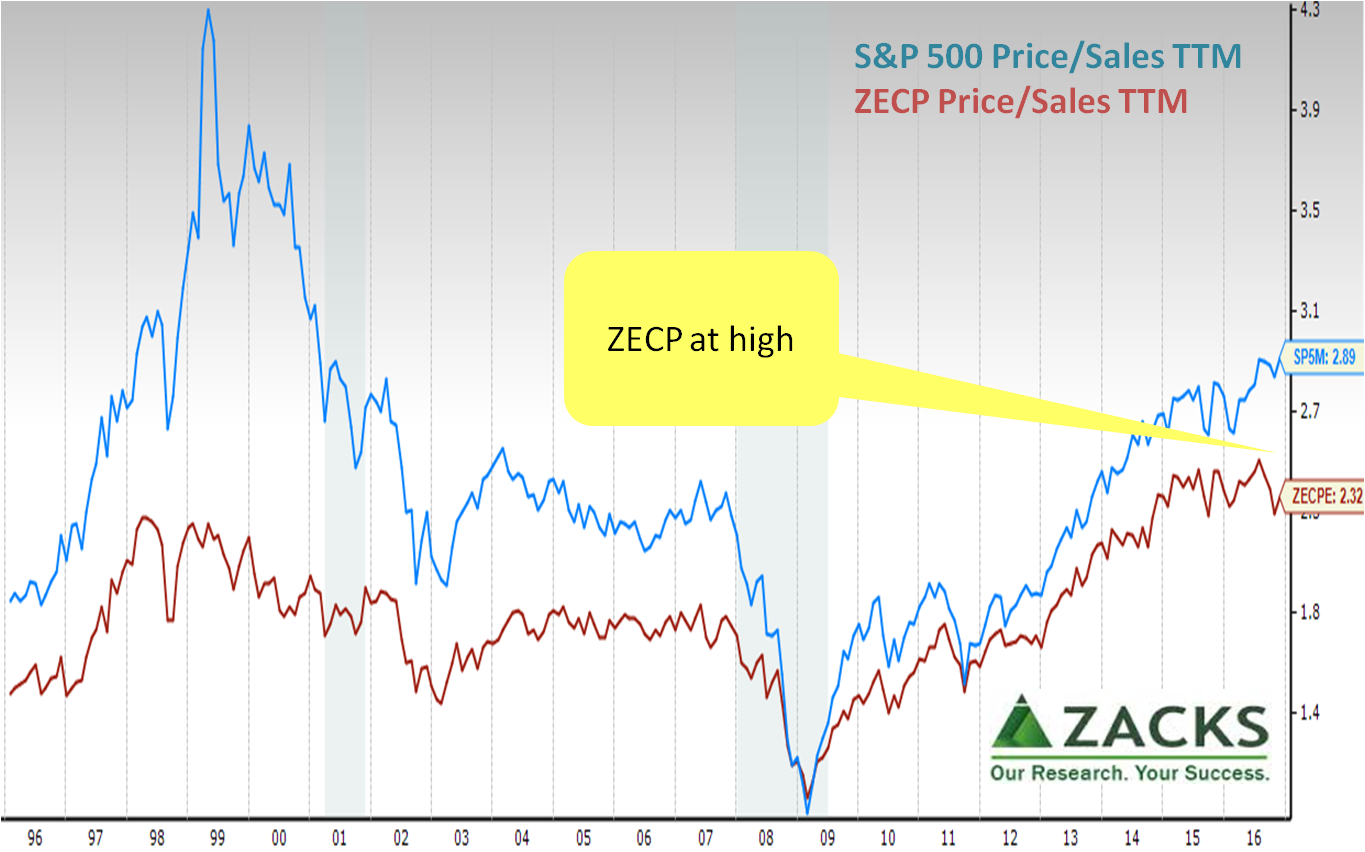

As sales are scarce as we showed in “How scary are sales? 3 insights tell the story,” consider Price/Sales for both the S&P 500 and Zacks Earnings Certain Proxy (ZECP) of 70-80 stable companies.

The S&P 500 is at highs other than the tech bubble. As ZECP excludes high-flying companies, it filtered out much of the tech bubble and is at highs today.

The S&P 500 is at highs other than the tech bubble. As ZECP excludes high-flying companies, it filtered out much of the tech bubble and is at highs today.

Each measure is individually limited…

- Price/tangible book, sales or free cash flow don’t account for decreasing needs for assets for production (especially structures and inventory) or improvements in management technique.

- Price/earnings is just not comparable over time as we’ve illustrated in To find better measures of value, look beyond broadsheet relics. In that analysis, notice the Price/Earnings-to-Growth (PEG) ratio at all-time highs indicating that growth estimates don’t justify today’s high P/E ratios.

Yet, together they paint a picture of an overvalued market.

Adding to the risk and fear is that today it is more difficult for a stock-picker to avoid this bubble than the tech bubble. Recall, from 2Q1995 to 3Q2000, there were only eight S&P 500 members with outsized growth — AES, Oracle, Qualcomm, Cisco, Celgene, Time Warner, EMC, and Biogen. And, several of those grew due to M&A. In contrast, the Fed bubble includes most S&P 500 members unless a company made a mistake or divested.

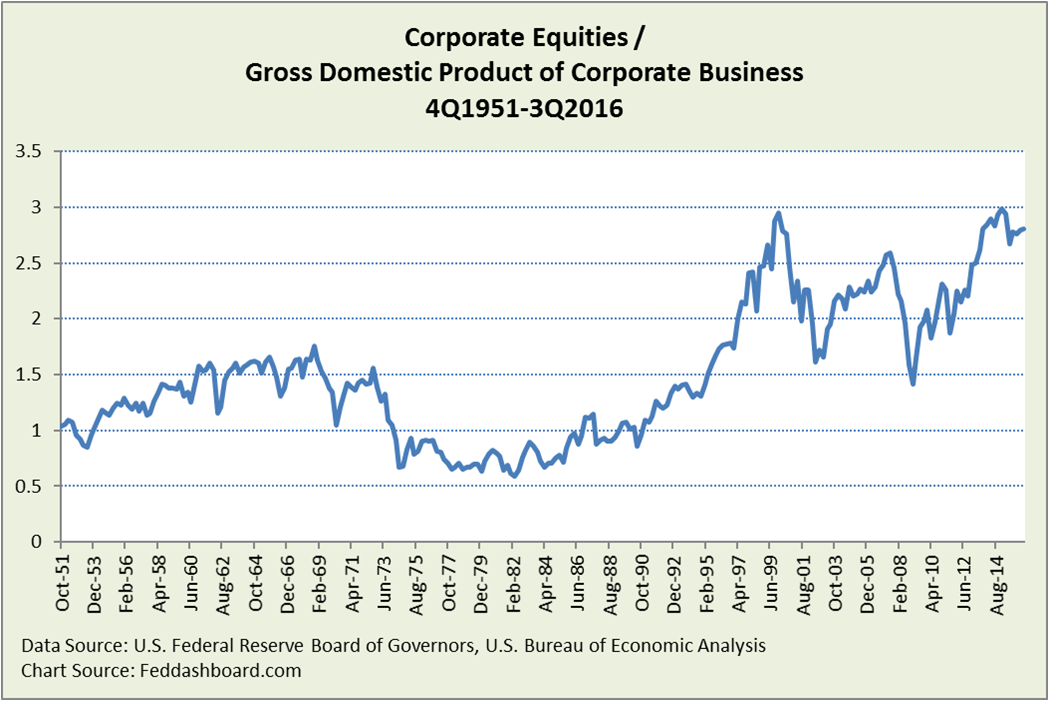

What matters most for economic growth is a price/sales ratio for our entire economy. This is because sales revenue is the source of flows that power the entire circular flow of our economy – wages, investments, and business payments for materials, services, interest and dividends. This is measured with the strain gauge of our economy, shown through the end of September, now higher.

Risk begins with the bubble

Risk begins with the bubble

Central banks’ failed attempts to use a “wealth effect” to stimulate the economy resulted in an equity bubble. Recall, the “wealth effect” was a two-part objective – increase financial asset prices and hopefully the tangible market (goods and services sales) would increase at the same pace. In valuation terms, if both increased together, this economic price/sales ratio would be stable. Central bankers got lots of price increase, but not enough sales increase – causing an equity bubble.

This bubble is both a first in history and the source of investor internal conflict – loving the gains and fearing a fall. Over a year ago we wrote that 93% of the rise in the market has been due to the Federal Open Market Committee.

This bubble is missed by those who primarily judge the risk in the price rise by number of quarters of expansion – wrongly applying historical trading or business cycle experience to the first in history effects of monetary policy. That view is a myth that ignores FOMC action.

Further, as we’ve illustrated in the past:

- Business cycles being cyclical is a myth ignoring causes.

- Equity risk premiums are not causes. They are mere reflections of monetary policy driving the “risk-free” rate.

Without new QE and fundamentals so strained, markets have largely moved sideways and overreacted to political events. While an opportunity for stock-pickers, it is a source of discomfort for many.

Danger of decision risk

Overreaction to political events, as with the Fed-driven bubble behavior is because traders and investors lack the tools to evaluate “decision risk.” Decision risk is not about:

- Recognizable patterns of tops and bottoms

- Another layer of derivatives

- Allocation tweak or even company fundamentals

In a fog, traders and investors both churn the markets with poor commentary and trades. This causes short-termism in companies and distrust in individual investors.

Decision risk is about a specific few people making high-impact decisions, especially decisions that are quickly felt. Consider the global impact of the swing voters serving on monetary policy committees of the European Central Bank, Bank of Japan, and Federal Reserve System.

Risk lies in anything with moving parts. Change, complexity, and fatigue are the catalysts of risk.

This risk grows in when decision-makers are in unfamiliar dynamics, influenced by emotions (especially fear), must select from only bad options, have little response time, or caught in a pre-programmed rule (from pre-World War I mutual aid treaties to options trading algorithms). When decision-makers are hampered, it makes guessing their decisions more difficult.

The Greek debt drama is one example. The saga of Greek debt is old, stretching back to the 1800s, at least the war of 1897. The 2015 act in the drama sprung from Greece’s 2004 admission of improper reporting. Danger grew because people were structurally blind to this long-unfolding story.

A new danger was how the circus that surrounded 2015 dangerously distracted European leaders from Russia and the migrant crisis (flowing from the conflicts in Iraq and Syria).

Bottom line

- The Fed bubble fueled twin anxieties – price growth that tempts investors to jump in while fearing a crash.

- Anxiety increases because of inability to evaluate decision risk and gauge impact

- Understanding these threats more clearly is the first step toward safer portfolios

Next in this risk management series, read “Biggest mistake managing risk.”

To learn more about how to apply these insights to your professional portfolio, business or policy initiative, contact “editor” at this URL.