Economists assume that lower interest rates increase business investment – all else equal. This assumption matters because it shapes interest rate policy and your returns. The problem is that all else isn’t equal; the interest rate-investment assumption hasn’t consistently held over time. Investors can bypass this problem by selecting companies based on business model.

“Low rates and higher asset prices should support household and business spending and investment through various channels.” – Federal Reserve Governor Jerome Powell, January 7, 2017. Governor Powell stated standard economics – if interest rates are lowered, then investment will increase. A web search reveals this in economics lectures around the planet. He then stated the data, “…low rates have clearly not produced a boom in corporate investment…”

Lower interest rates haven’t created a boom in fixed investment for at least three reasons:

- Federal funds rate increases don’t proportionally flow to credit markets

- Business investment decisions are based on more than interest rates, including net present value factors

- Fixed investment required for production has been declining, mostly buildings

First, federal funds rate increases don’t proportionally flow to credit markets

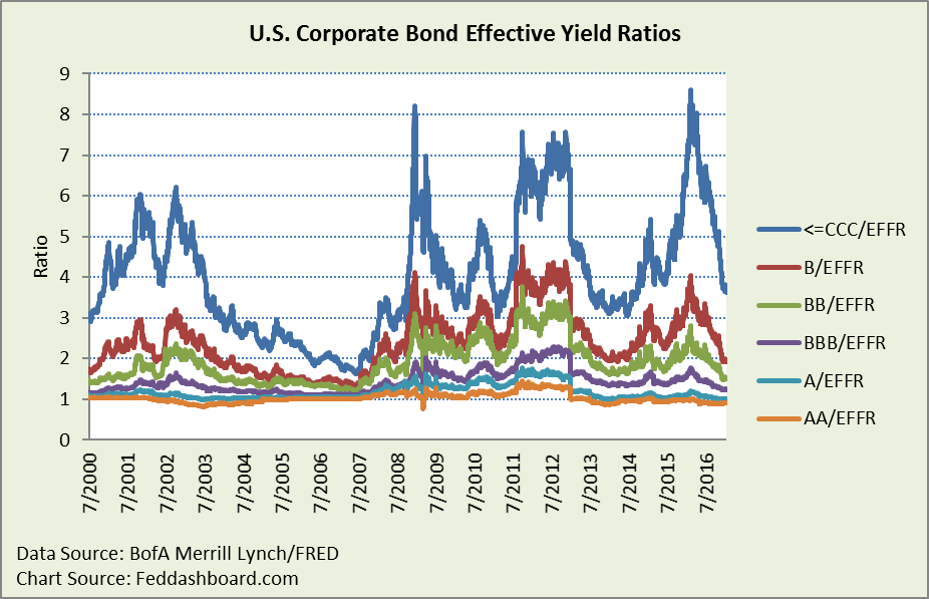

For the effective federal funds rate (EFFR) to work well as a monetary policy “transmission channel,” it should trigger proportional changes in public debt markets and loans.

- In “Smarter bond strategies revealed in secrets of credit spreads,” it was shown that credit classes don’t move in sync with each other.

- Here, we see bond to EFFR ratios recently falling – that’s good news for bond issuers, but bad news for the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) as transmission of expected and actual EFFR increases has been dampened as EFFR passes through credit classes.

More, extraordinary monetary policy increased volatility in the three-month U.S. Treasury bill market by six times.

More, extraordinary monetary policy increased volatility in the three-month U.S. Treasury bill market by six times.

In private lending, credit pricing and regulations have kept lending rates historically high relative to EFFR.

Second, business fixed investment decisions are based on more than interest rates.

This is the reality that slaps economics students when they take their first finance course. Consider what goes into a net present value (NPV) formula used for making investment decisions:

- In the denominator, the company-wide weighted average cost of capital (WACC) is calculated. This includes debt, equity and retained earnings. Debt includes public and private. Different rates apply depending on what backs a debt, seniority and term. Then there is tax treatment, such as for leases.

- To dampen impact of rate increases, corporate treasurers try to lock in low cost debt. Capital management might also include debt-equity shifts as described in “Don’t rebalance your portfolio without first checking these 3….”

- Also in the denominator, time value of money and company-wide risk are reflected. Risk includes business environment, customer, competitor and regulatory. Uncertainty (risk that can’t be easily measured) is also roughly reflected.

- In the numerator, the proposed investment-specific cash flows are calculated and adjusted for time, risk and uncertainty.

Low interest rates don’t help if companies face high risk and uncertainty. Central banks that cause volatility and uncertainty have been defeating their own interest rate actions.

Of course, companies eager to invest have found their access to credit constrained by both risk-averse regulators placing higher risk weights on business loans and a more risk-averse bank underwriting and loan approval process (particularly impactful to small and middle market companies).

These decision aspects break the assumed interest rate-investment relationship.

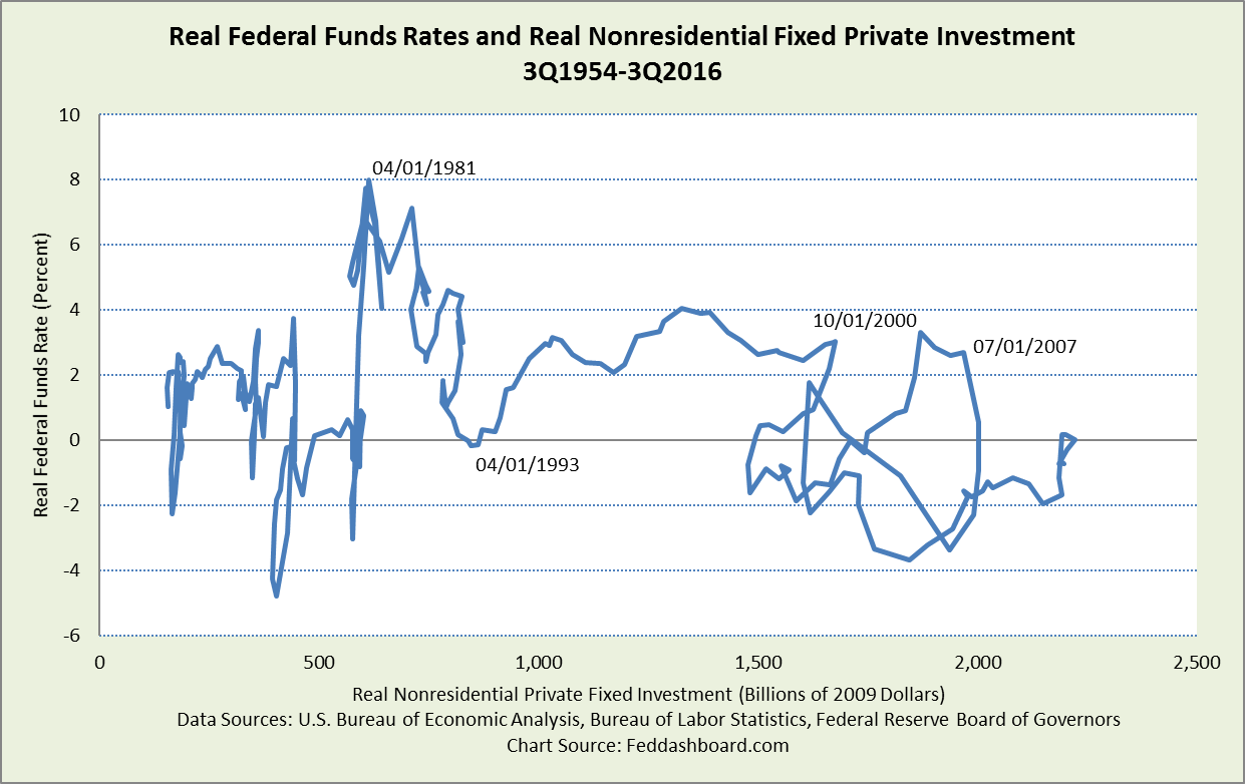

This is reflected in the time track of the real EFFR to real nonresidential gross private fixed investment.

Two, thirty-year eras are seen:

Two, thirty-year eras are seen:

- From the early 1950s to early 1980s, more volatility in real rates and inflation, and slower growth. The interest rate-investment relationship frequently flipped.

- From the early 1980s to present, less volatility and more growth. Real rates fell in the 1980s following the Fed’s aggressive efforts to break the back of inflation, the global oil glut and dramatically falling electronics prices described in “Epic Econ: “Breaking the back of inflation” – lessons for today.” This was followed by the 1990s with increasing rates and investment that flowed into the three great bubbles – dot com, mortgages and Fed. Bubble expansion and collapse is seen where the time track swirls and the relationship flips.

Real EFFR plotted with one-year percent changes in investment (not shown) from 1954 to 2016 reveals a small and weak positive relationship between rates and investment – the reverse of the standard assumption. No relationship is observed since 1999 in a world of increasing cash and decreasing need for fixed investment for production.

Third, fixed investment required for production has been declining, mostly in buildings, also in equipment. This was described in prior analyses, including “It’s not secular stagnation; it’s the tech and trade transformation.” Causes include smaller footprint manufacturing, multi-functional, smaller manufacturing equipment (think industrial power generators and robots) and shifting industries of emphasis.

Performance improvement in equipment relative to price has been underestimated so investment isn’t as weak as measured.

Opportunities for investors

- Evaluate interest-rate sensitivity of companies based on business model, NPV factors and capital structure

- Evaluate changes in fixed investment needed for a given level of production

- In banks, evaluate changes in loan types, fee income and regulation

To learn more about how to apply these insights to your professional portfolio, business or policy initiative, contact “editor” at this URL.

Data Geek Note: Nonresidential private fixed investment used to avoid conflating residential causes such as demographics and mortgage derivatives, and from shorter-term forces that swing inventory