“No one can see a bubble, that’s why it’s called a bubble” is a myth. Like kids blowing bubbles on a summer day, bubbles are bubbles relative to a reference point — like the base of a kid’s bubble pipe. Financial asset bubbles are revealed when compared to tangibles such as sales or assets.

Kids are good at spotting the unusual – like the biggest cookie compared to others. A financial bubble is born when the price of a financial claim (e.g., stock or bond) exceeds the value of the tangible (e.g., hard asset or cash flow) to which it lays claim.

It’s easy to see a price increase, but the question is whether a tangible change justifies that price increase. So we spot financial bubbles by understanding causes.

Historically, bubbles tend to be brewed by some combination of excessive optimism and liquidity. That liquidity might flow from tangible economic health, monetary policy or credit.

Pure financial bubbles are relatively easy to see because the underlying tangible asset really doesn’t change. Instead there is a cash flow to that asset class. Causes of these inflows tend to be either “follow the leader” or “flee the fear.”

- “Follow the leader” bubbles tend to originate in government tax, spending, regulatory or monetary policy. The mortgage bubble was an example – tax-deductable mortgage interest, subsidies to housing and encouraging low income home ownership. Our current equity bubble started with the Federal Reserve (Fed) seeking to create a “wealth effect” that they hoped would encourage broader spending and investment — it didn’t happen. Follow the leader can also be caused by retail investor exuberance (as before the Great Recession) or trader herd mentality.

- “Flee from fear” bubbles are often caused geopolitical events and policies that trigger people to seek safety. Safety in recent years has included U.S. Treasuries and equities.

Financial bubbles are more easily spotted with three steps:

- Compare a financial asset measure to more tangible values such as sales, production or nonfinancial assets.

- Determine causes of past moves and use scenarios to discover new causes.

- Use measures of risk matched to the nature of risk. For example, as we’ve written in the past, don’t use linear statistical measures such as correlations on nonlinear data. Value at Risk models over-rely on trading history, and mostly ignore causes and deeper trends.

Evaluating “excessive optimism” requires another step – considering whether that optimism is backward or forward-looking.

- Backward-looking is about whether a past, tangible growth rate will continue. Past growth can be anything from what European trading powers experienced in the 1600s to optimistic statements from a few years ago that S&P500 companies could continue to cost cut their way to growing EPS. Digging through layers of causes is rewarding for those who take the time.

- Forward-looking is more difficult because it requires valuing tangible assets and cash flows that are contingent on business outcomes such as: new technology achieving design objectives, market development or competitive survival. The South Sea, railroad, telecom and dot com bubbles had this in common.

- Political analysis is needed when causes are related to government policy such as U.K. debt with the South Sea bubble, and U.S. regulatory policy with railroads and telecom.

- Company-specific analysis is needed to find winners and losers as in railroads, telecom and dot com.

- These bubbles spur innovation in trade and/or technology. When they are fueled by more cash than credit, the bubble bursting does relatively little economic damage as we saw in 1999 compared to when the credit-fueled mortgage bubble burst.

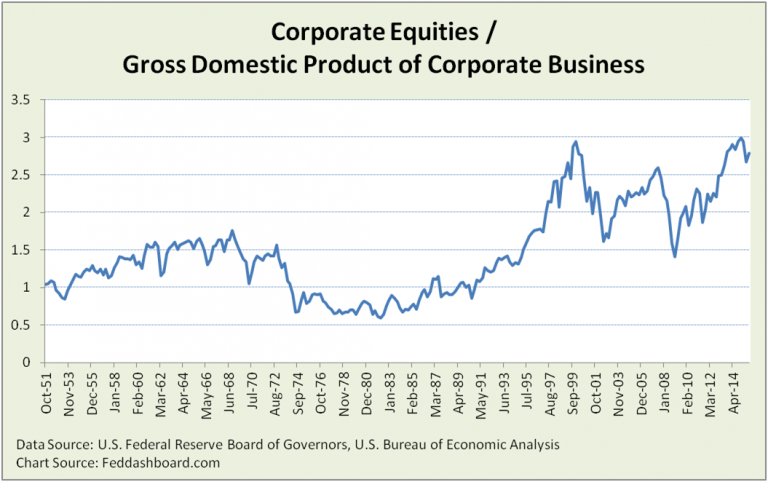

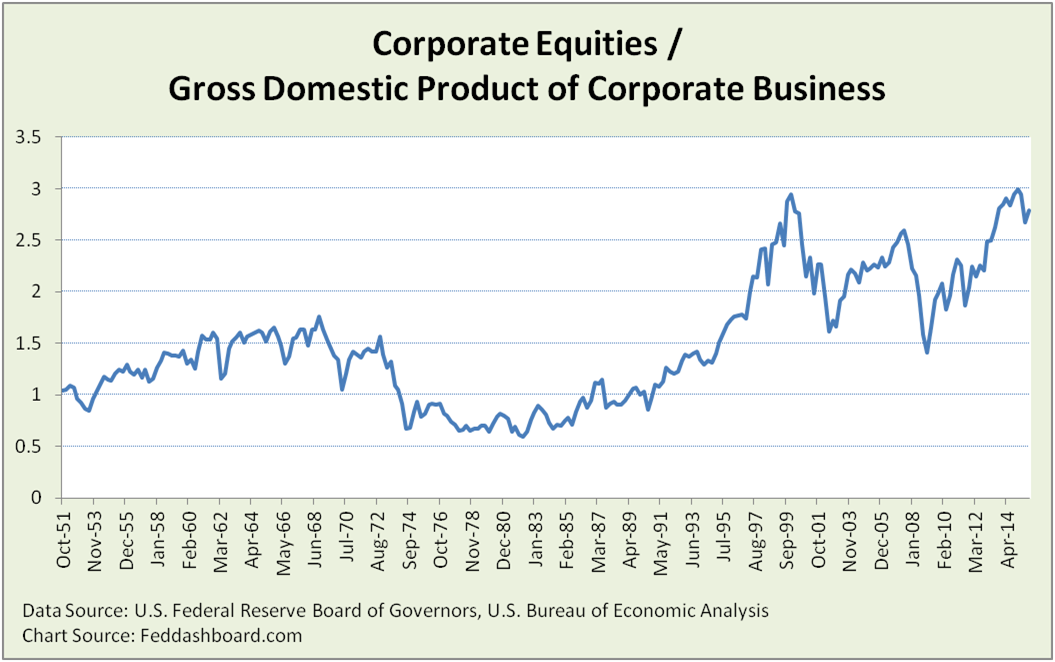

We’ve previously illustrated a range of these bubbles. For the mortgage bubble, we highlighted the “Treacherous Triangle” pattern. Fundamental bubbles have been illustrated our Market Fundamentals section, often with visualizations from Zacks Research System. At the broadest level is the Strain Gauge ratio of the public equity markets to business production. It reflects how far equity market prices strain above the tangible goods and services market. Just as the valuation of a retail store can be excessive for a given level of sales, this strain gauge values our economy.

This is the 1Q2016 view based on most recent Fed data. Using the 2Q2016 total GDP estimate and current S&P500, this strain gauge is back at all-time highs.

This is the 1Q2016 view based on most recent Fed data. Using the 2Q2016 total GDP estimate and current S&P500, this strain gauge is back at all-time highs.

An important difference between today and 1999 is that today’s bubble is far broader than tech companies. This means more investors will get hurt if this ends badly.

A criticism of this particular strain gauge is that it is effectively a price/sales ratio for U.S. corporate business and that price/earnings ratio is a better comparison. Three replies:

- This same criticism was offered several years ago coupled with forecasts that EPS growth would continue and cost-cutting would drive top-line growth – both now clearly false

- Price/earnings ratio was never logically valid because it excluded change in growth rates and included the fallacy of past performance. More on this at “To find better measures of value, look beyond broadsheet relics.”

- Even if price/earnings ratio was perfect at a company level, it’s wrong for the economy. Why? In the circular flow of our economy, sales enable business to pay wages and buy inputs from other businesses.

There are three ways this bubble could resolve as we discussed two years ago.

- Tangible economy could grow reducing the strain without the need for equity prices to fall — this was Fed’s hope when they created their “wealth effect.”

- Rapid decompression due to

- Market: insufficient liquidity or inability to deliver securities

- Strain exposed, spooking traders, especially as traders are uncertain how to read these markets

- Slow leak due to

- Interest rates — affects on savers and debtors

- Households — demographics, savings, medical & more costs

- Business — cash haves and have-nots

- Scarce resource (commodities and input goods) — differential affects on prices

- Government — debt and regulation

- Geopolitical and pandemic

How far might the market fall?

- Looking only at the tech and mortgage bubbles bursting, both fell to the high-side of 1960s levels on the Strain Gauge

- Other factors that will shape the fall include: 1) memories of protection provided by the 2008 bailouts, 2) central bank “puts” to “backstop” the markets, most recently reinforced by the Bank of England, 3) how recently revised derivative contract language, accounting rules and regulation will interact under strain (a topic with far too little study), and 4) which trading approaches will dominate in times of stress and how those traders will interact in their prisoner’s dilemma.

- Clues are gleaned by studying any unusual volatility.

Actions for investors

- Think like a kid when evaluating bubbles – compare to an underlying, more tangible measure of value

- Revise asset allocations using strain gauges and scenarios that include the triggers listed above

- At the sector level, be alert for sentiment traders increasing bubbles with rotations unsupported by fundamentals

- Change to risk measures that are appropriate to the data pattern (e.g., nonlinear), and potential causes of slow leak in or bursting of a bubble

- Study volatility for clues to what might happen in “the big one”

Action for the Fed:

- Recognize the magnitude of the current bubble and normalize without increasing bubble risk