28 August 2014

Avoiding excessive distortions, rather than driving demand, is a growing monetary policy debate; this includes the rules-based monetary policy debate. Any approach is complicated by traps compared to available tools for managing prices.

Sound bites confuse the conversation by confusing aspects of price changes. To clarify:

- “Inflation” – strictly speaking – is about general price increases across goods and services. This is in contrast to a specific price increase resulting from changes in supply and demand for a specific good or service.

- Specific supply and demand changes include scarcity of workers (i.e., right number, skills and place), capital (e.g., plant or equipment) or input materials (e.g., energy or agricultural) and government action (taxes, subsidies or regulation on production).

- Supply and demand adjust more or less quickly depending on the factors involved (e.g., time to build a factory)

- Beyond individual supply and demand adjustments, broader inflation is driven by monetary policy. This is described in the quantity theory of money and other views.

For more, see Better investing by better understanding sources of inflation, June 2014

For managing inflation – again, strictly speaking as general price increases – the Fed is king of the hill. Yet, even here the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is facing potential limits to its tools. Two include:

- Global world of central banks – including the European Central Bank and Bank of Japan pursing more expansive policies as the FOMC slows.

- Behavior of money velocity as the structure of transactions change, including electronic money and barter. This is a particular concern given mountains of cash on the sidelines. The FOMC received a taste in January 2013 as cash on the sidelines amplified the start of the third round of the Large Scale Asset Purchases (LSAPs, aka, “QE3”).

Yet, we’ll leave these heady global monetary thoughts for something simpler – patterns in specific price changes.

It helps to tell the story through personal pocketbooks — price changes faced by households.

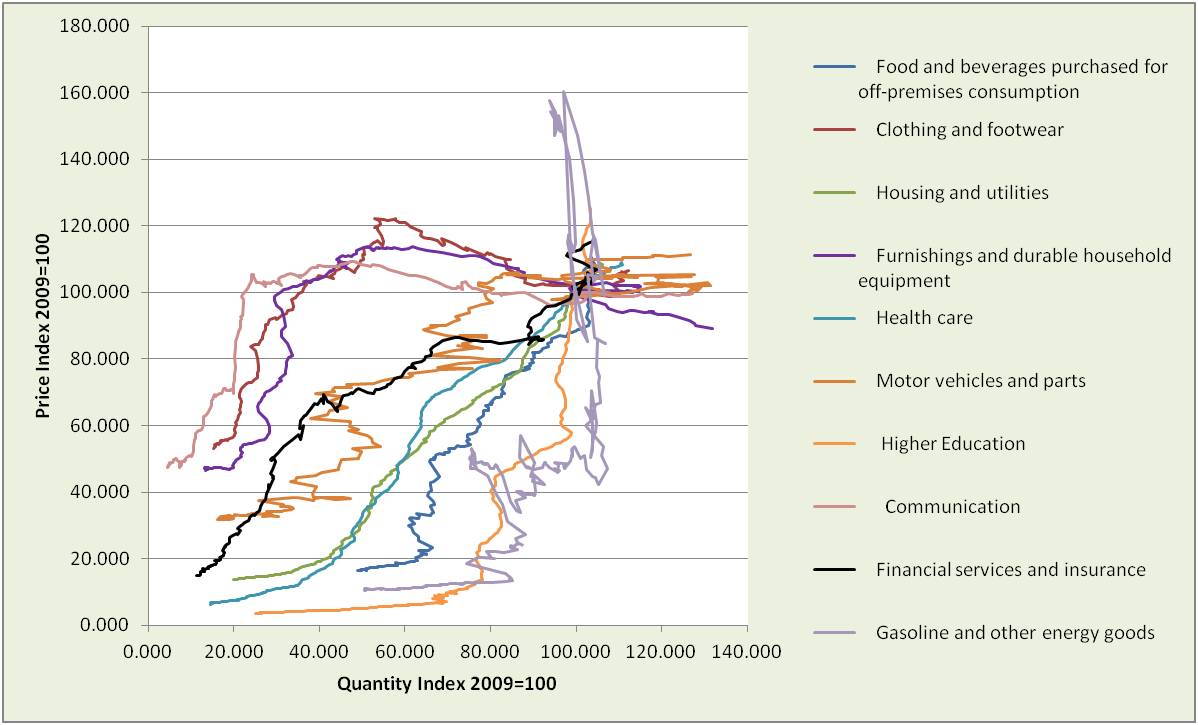

The pictures below are scatter plots for often-watched household expenditures, selected from dozens provided by U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA).

Presented in a standard supply and demand format (price and quantity), the lines are the moving intersection points of supply and demand each quarter from 1Q1959 to 2Q2014. Lines converge in 2009 simply because BEA indices are set to 2009.

The more vertical is a given line, the more price increase relative to output. The price increase includes both affects of supply and demand, and general price increases related to monetary conditions.

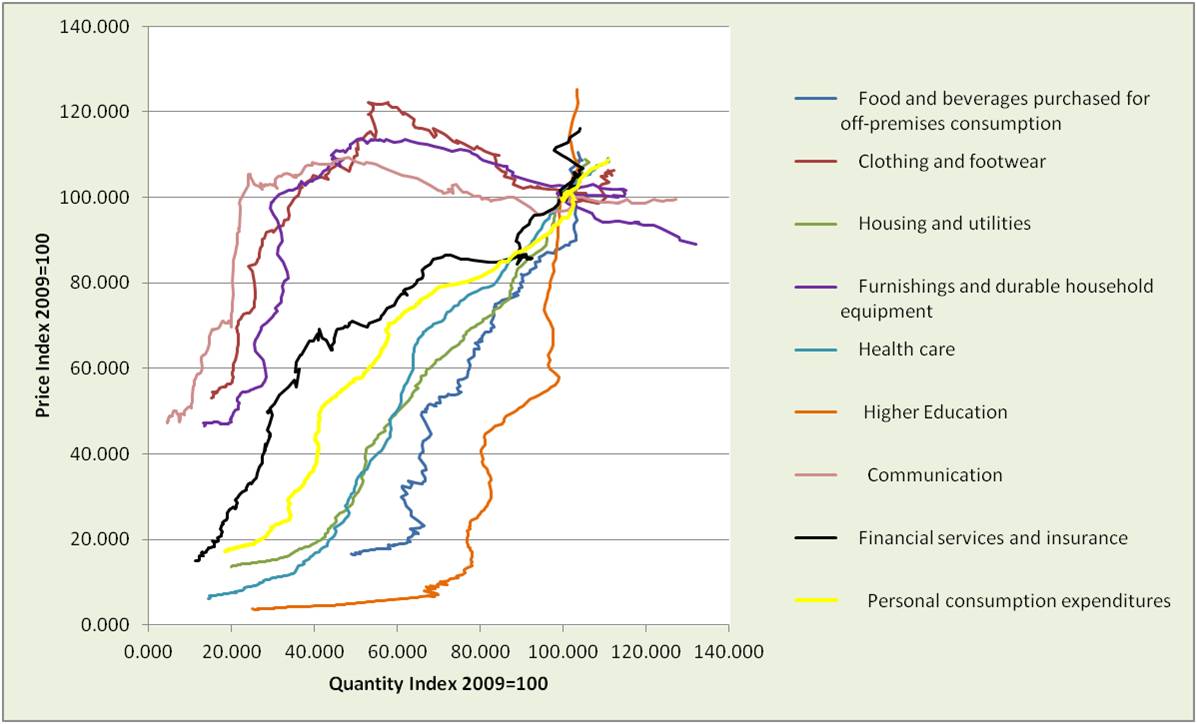

Second picture is the same as the first except that for visual clarity two categories are removed. Motor vehicles are removed because of significant quantity fluctuations and gasoline because of price fluctuations. Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) is added as a reference.

Second picture is the same as the first except that for visual clarity two categories are removed. Motor vehicles are removed because of significant quantity fluctuations and gasoline because of price fluctuations. Personal Consumption Expenditures (PCE) is added as a reference.

Differences illustrate potential traps for the FOMC:

Differences illustrate potential traps for the FOMC:

- Acting on price increases higher than the PCE average could excessively tighten and risk distortion in other areas of the economy. Doing nothing based on the price increases lower than PCE average, could cause the reverse problems.

- Acting without sufficient understanding of import trends. For more please see the story of the 6 dots, April 2014

- Using monetary policy to address price increases not caused by monetary policy (LSAPs or interest rates) would likely be futile or distorting. For example, price increases related to government spending and tax subsidies (e.g., higher education, medical care and housing), or trade policy.

For policy-makers, this illustrates the need to understand root causes, use the right tools for the job and be statesmen in the sense of collaborating in regulatory, tax, fiscal and monetary policy.

For investors:

- If the objective is to be active in sectors subject to distortion, understand these dynamics to influence in/out decisions.

If the objective is more conservative, then avoid areas of distortion and focus on company business models that are less influenced by monetary policy traps or triumphs.